Autonomous Technologies and those last “five percent”…

A recent article on nationalacademies.org (which certainly sounds like a solid reference) has as its title “Driverless Motor Vehicles: Not Yet Ready for Prime Time” (link below). Since an abundance of media space too often is given to press releases from technology companies, which are then echoed by techno-optimistic bloggers, this was a title that caught my eye. While it would be nonsensical to deny the achievements of technological progress and a mistake to minimise them, there are still reasons to remain cautious about some of the promises made by visionaries of technological progress. If they all would have come through as envisioned, I would already in teenage years have been flying to school in a jetpack and friendly robots would have guided me to fully immersive learning experiences (instead of having to bicycle to school and watch the teacher write on a blackboard – and yes, I am that old, blackboards and overhead projectors were the prime means for display of information back then).

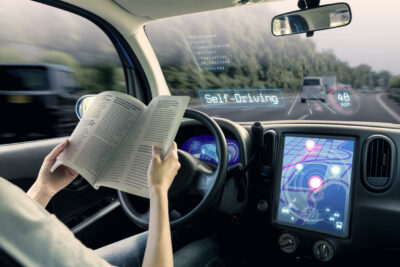

The article acknowledges that the current death toll in traffic could be significantly reduced with increased use of automation for road transportation. However, it does pose two questions often asked in regards to automation: 1) What happens if the automation fails? and 2) What if the automation has to handle a situation that has not been considered by its designers? These questions has been asked throughout the history of automation, robotics and AI and it has been explored by researchers and others thinking about the potential and limitations of technology. In the article, these questions are focused on fully automated vehicles, i.e. self-driving cars but it brings up many aspects which are equally relevant for aviation.

The article goes on to discuss the challenges to achieve the vision of a fully automated road transportation system and references the experiences of automation in aviation. The point made is that in aviation, automation has been an ongoing process for decades, that this has been in a less complex environment than road transport and that still today pilots are not expected to be replaced any time soon. I am not sure that I agree with either of these statements, given the complexity of any airspace environment, especially close to a major airport, and the current developments towards single pilot operations. But perhaps complexity can be a matter of perspective.

Developing autonomous vehicles is, according to the article, more challenging than previously envisioned and will take longer than many of its proponents advocates have anticipated. Also, the many Human Factors challenges experienced in aviation are mentioned, with implicit reference to accidents and experienced related to automation. Special emphasis is placed upon the difficulties of mixing autonomous and human operators and the potential failures of automation. The recent Boeing 737MAX accidents are brought up, so is the “Miracle on the Hudson”, as a counterpoint. While providing a less positive perspective than often encountered in texts about automated transport, it is useful to read this perspective and consider the remaining obstacles to this vision.

The point of the article may be supported by the experience in daily life of interacting with the “chatbots” often used these days for customer service. Even if it is not made clear to us that we are speaking to a bot, it does not take long (a non-standard question is usually enough) until we realise that we are not chatting with another human being. For a range of simple questions (location, opening hours, ticket prices etc.) we would probably not have known the difference. But for anything beyond this they usually create nothing else but frustration. Even as these chatbots gets far more advanced, those last five percent of difference to a human may still be challenging to resolve. The same may prove to be true for both driverless cars and pilotless planes.

Link to article:

Driverless Motor Vehicles: Not Yet Ready for Prime Time

Planes vs. Trains – A complex issue

Comparing planes to trains could be seen as a topic better avoided for those of us who work in the aviation industry. Because it is a topic about competition that has already affected the industry in a number of countries, or has the potential to do so. The topic is not new but given the relatively slow progress of high-speed trains in recent decades it has been more of an evolution than revolution. The arguments for and against each mode of transport are also not new, with time of travel, environment, accessibility, infrastructure and others being part of them. Comparing planes to trains can unfortunately become more political than pragmatic and polluted with arguments that may not be as complete and transparent as they should be. This situation is made even more difficult as different lobbying groups may cite research funded by the respective group. In this post we will try to keep it simple, as a few examples will be brought up to illustrate the topic, and some considerations in relation to the topic will be presented.

The development of high-speed trains is probably best known in connection with the TGV trains in France or the ICE in Germany. Many would also have heard of the large scale development of a high-speed train network in China. However, the highest number of kilometers of high-speed railway in Europe is in Spain (link to article below). This has been a slow development over recent decades, but as more operators are competing on this network there is an expectation of a coming increase in passengers. Still, even today and with this competition, the flight between Madrid and Barcelona is the busiest short-haul route in Europe. This may however change as two new low-cost train companies have begun operations this summer, offering basic fares below 10 Euros for the trip between the two largest cities of the country.

Another case study can be found in Italy (link below). Here, the evolution of high-speed rail transport is seen as a reason for why Alitalia could not survive (the dysfunctionalities of Alitalia and competition from low-cost carriers were probably other important reasons). The main travel route between Milan and Rome is three hours by high-speed train, which should be compared with a drive to the airport, checking in an hour before a flight, an hour in the air and then another drive to get into town. The result has been that passenger numbers on high-speed trains in Italy has gone from 6.5 million in 2008 to 40 million in 2018. In 2018 69% of all passengers going between Rome and Milan used the train, which represented an increase of more than 7% over three years, while air travel lost about the same amounts of passengers in the same time period and was left with less than 20% of the market on this route.

These examples are typical for the competition situation between high-speed trains and air travel. Comparisons between the two on short-haul routes (link and link) shows similar total journey times. While there used to be a cost gap in favour of planes, this gap shrinks as soon as there is competition on the high-speed train routes. Service levels in terms of frequency and onboard service has previously been an advantage for air travel, but this gap can also be reduced by train operators. With concerns about the environment favouring trains, the results is that flying comes under severe competitive pressure from high-speed trains.

However, these are the easily visible arguments. There are other arguments to consider as well and foremost is the large-scale investment cost required for high-speed rail transport. There have been reviews of this (such as link and link) and to quote from the first link, an analysis from Leeds University: “Decisions to invest in this technology have not always been based on sound economic analysis. A mix of arguments, besides time savings, strategic considerations, environmental effects, regional development and so forth have often been used with inadequate evidence to support them.” To summarise further arguments in the same paper, the investment cost for high-speed rail can be motivated only in the unusual circumstances of low construction costs plus high time savings (because of poor existing rail lines and inadequate services on competing modes of transport), and with for a level of at least 6 million passengers per year (for more typical construction costs and time savings, 9 million passengers per year is required).

In another report (link), the following conclusion is drawn related to the environment: “Investment in high-speed rail is likely to reduce greenhouse gases from traffic compared to a situation where the line is not built. The reduction, though, is small and it may take many decades for it to compensate for the emissions caused by construction. In cases where anticipated journey volumes are low, it is not only difficult to justify the investment in economic terms, it is also hard to defend the project from an environmental point of view.” This brings in an environmental aspect on the sizeable investment needed for high-speed rail.

So, while not denying any of the advantages of high-speed rail transport, the question is if the vast resources required for this mode of transportation could be used differently and more efficiently to achieve the same goals. Also, the time frame for the project is important – a comparison of the different modes of transportation today may be irrelevant in 20 years due to new innovations. And for large projects like these it is often public funds that are used and which are at risk if the project is not successful, not private funds, as is more common in aviation. As an example, if even some of these funds in recent decades had gone to develop alternatives to jet fuel (sustainable fuel, batteries, hydrogen) perhaps aviation could have been carbon neutral already? This demonstrates that the full picture of a long-term and complex issue as this one must be thoroughly investigated, preferably by a third party entity. In the end, it is likely that high-speed rail is the best solution in a number of scenarios, but equally likely that there are many scenarios considered today where it will not be the best solution. Let us hope that pragmatism will be what decides which is the best solution for different scenarios.

Link to articles:

Spain’s high-speed railway revolution

How Italy’s high-speed trains helped kill Alitalia

Anders Ellerstrand: Procedures 5 – As a Normative Function

This is the fifth and last eposiode of a series about procedures by Anders Ellrestrand. The previous episodes can be found here: 0 – Introduction, 1 – Design Process, 2 – Memory Aid, 3 – Training, 4 – Collaboration.

Your procedures constitute your organisational baseline. They are the standard and the norm. By that, procedures also limit the behaviour – of staff, the organisation, and of the system.

By this it is possible to monitor the organisation and to notice any variability. There is a possibility to notice the gap between ‘work-as-imagined’ and ‘work-as-done’. We have already established that there will always be a gap but also that it is good if the gap is not too large. A large gap can be the start of a system that drifts into areas where hazards are not pre-identified, and where the associated risks are not assessed and mitigated.

In many organisations, the distance between ‘the blunt end’ (management and support functions) and ‘the sharp end’ (operators) is too large. The gap between WAI and WAD goes unnoticed until a time when there is an incident and where an investigation reveals ‘unacceptable’ non-compliance with procedures. When there is an investigation into an incident, there is often a pressure to quickly find the cause and then to establish an action that will stop re-occurrence. It could be tempting to not spend the necessary effort to find all the contributing factors, but instead point at the human at ’the sharp end’; the ‘human factor’.

If the gap between WAI and WAD instead is discovered as a result of closely monitoring daily, normal operations, it could be easier to ask the relevant questions and consider more options. Are there procedures in place that does not make sense to the people supposed to use them?

In a row of posts, I have pointed at several areas where procedures are important, helpful and where they are necessary for an organisation to function. However, procedures can also make work more difficult. Procedures can restrict flexibility and make necessary adaptations more difficult or even impossible. When procedures are too strict/limited it can become necessary to deviate from them to be able to get the work done.

There is a debate about procedures (and rules and regulations) and you can identify two hard-core schools:

• Procedures are the norms of an organisations. If they are fully complied with, work gets done in a correct and safe way. Most, if not all problems, come from non-compliance, often labelled as ‘human error’.

• Procedures are part of a top-down control and limit the human ability. Procedures are obstacles that makes it more difficult for people to address real-world problems in an ever-changing and complex world.

As usual, the truth is somewhere in a large grey zone between these positions. We should aim at writing procedures in a way that provides the necessary flexibility, for the operator to be able to adapt to different situations, while still following the procedures. At the same time, the procedures must maintain their role of limiting behaviour, maintaining their normative function.

This is, of course, much easier said than done.

Gary Martin: Air Cargo and Security

This post is by a new visiting writer, Gary Martin, Avsec Training Manager at G4S SECURE SOLUTIONS in IRAQ. I am grateful to Gary for adding the security perspective to the Lund University School of Aviation blog. We are always welcoming fellow aviation professionals to post on the blog and to add perspective, new information and sharing of practice in the industry.

This article follows up from a comment I made to a post that my good friend and ex-colleague Nicklas Dahlstrom had written about air cargo (link) and the important role that it played during the COVID-19 pandemic. In my comment I highlighted the fact that air cargo is viewed as the weakest link within aviation security and that it was being exploited by drug smugglers. They would facilitate their illicit trade in moving narcotics through borders with limited checks as they were in shipments of COVID-19 vaccinations and or PPE (mask, gloves etc) which were urgently required in many countries around the world.

I went on to say that it could have been very easy for these narcotics and other illegal contraband, to be replaced with an Improvised Explosive Device (IED) and therefore bring the aircraft down, potentially over a heavily populated city. Can you imagine the devastation not just to the city below but to the entire cargo network, more especially during a pandemic when cargo was so critical in moving PPE and medical supplies. With passenger traffic dropping 63% during the first 10 months of 2020, cargo saw a relatively smaller reduction of 11%, with some airlines even choosing to use passenger aircraft as cargo due to the high demand.

Let’s go back before the pandemic and look at air cargo and the view that it was and possibly still is the weakest link. With advances in passenger screening after incidents such as with Richard Reid, the “Shoe Bomber” and Umar Farook, the “Underpants Bomber”, and the 2006 liquid bomb plot, there were various pieces of equipment, processes and procedures that were introduced to combat these new and emerging threats from the terrorist.

It wasn’t really until October 2010 and what has now become known as the cargo bomb plot that emphasis really switched to the security measures that were in place for air cargo. Two packages were loaded onto a UPS and FedEx cargo aircraft. The cargo itself were printer toner cartridges addressed to synagogues in Chicago originating from Yemen. That in itself should have been an immediate red flag. Ship printer cartridges from Yemen to Chicago. Now we all know that Yemen is the central hub for printer cartridges, right? Both packages had been on several passenger aircraft as part of their trip to Chicago. One was eventually detected at East Midlands Airport, after around 10 hours and several conversations with Saudi and Dubai authorities who had already found the other device in Dubai.

After this event, legislation had to change, and it did. Europe introduced ACC3 which was designed to improve screeing of cargo from a third country airport flying into the EU. There were also other changes to the screening of cargo, with the introduction of the use of dogs for detecting explosives and vapour detection technology. The whole supply chain was revamped, with known consignors and regulated cargo agents having more stringent security controls in place. Cargo screening is now finally catching up to the same level as passenger screening, there may still be a bit to go, but it is certainly going in the right direction.

According to IATA, airlines transport over 52 million metric tons of goods per year, representing more than 35% of global trade by value but less than 1% of world trade by volume. That is equivalent to $6.8 trillion worth of goods annually, or $18.6 billion worth of goods every day. As you can see, cargo is a very lucrative business and one where security controls must be as tight and secure as they possibly can be, even more so in the current climate when the transportation of pharmaceutical cargo is especially important for us all.

Anders Ellerstrand: Procedures 4 – To Enable Collaboration

In the previous post (link), I argued for the possibility that instructors on a training institute interpret procedures differently and thus train students differently. Having similar ways of interpreting and applying rules have a value and that is especially true when you look at procedures as a most important tool for collaboration and for harmonisation.

A team typically works better if the members know each other well. It is also good if you agree on a row of things, such as what are the goals to achieve, what standards to apply, what methods work best and so on. Procedures take care of some of that. By having good procedures, that everyone in the team adhere to, you will know what to expect from your co-workers, and this makes life easier. The work can be done in an efficient way.

We can find an old example by looking back more than 80 years, to the second World War, when the last obstacle for Germany to conquer Europe was the British Royal Air Force. You may have the view that the German military was extremely well organised and efficient. But the German Air Force were very far from being as efficient and well organised as the RAF.

One example is the ‘Dowding system’. It controlled the airspace across the UK with an integrated system of telephone network, radar stations and visual observation that made it possible to build a single image of the current situation in the entire airspace.

One of the enablers was procedures! Although the airspace was divided in several sectors, the same procedures applied. One effect was that you could move staff between sectors without re-training. Another effect was very efficient collaboration. The end effect was of course the ability to get the fighters airborne at exactly the right time and in the right numbers to provide a persevering and efficient air defence that eventually had Hitler withdraw his plans for occupying Britain.

I think most of us could fine our own examples. I worked in an ATC Centre where most ATCOs agreed that it did not matter what other ATCO they worked with, since there was a general understanding and agreement on how to interpret and apply procedures. I heard ATCOs saying that they were happy with their procedures – they made sense and were useful.

However, I have also visited an ATS unit where ATCOs were divided into teams. The ways of working developed in a way that the teams became quite different. If one ATCO temporarily had to change team, they found that quite difficult. Suddenly they did not know what to expect from their colleagues. That uncertainty influenced efficiency, and perhaps even safety.

The organisation of the work force in teams probably had a role to play here, but I also believe that very well-written procedures could have helped to improve the situation. Procedures that make sense and are useful are more likely to be used in the intended way. That could also contribute to good collaboration.

Air Cargo – An important but less famous part of the aviation industry

There are things that “everyone” knows that seemingly very few people actually do know. The other week this blog brought up such a thing, namely who is flying as passengers and who is not (link). For experts in the aviation industry and academia this was an issue that probably is well known, but perhaps not by many more than those experts. Today, we are bringing up a similar topic – the transport of goods via air around the world, i.e. air cargo. As much as it may be argued that “everyone” knows also about this topic, air cargo is probably not something that many has a good knowledge about. Even those who work outside of air cargo in the aviation industry often do not know much about it. So, here is a small overview of this crucially but less famous part of the aviation industry.

Airlines and traffic with passengers get most of the attention in the aviation industry, but the pandemic has showed how important the cargo part of the industry is. Still, it is not easy to find numbers that demonstrate this importance, at least not in comparison to passenger traffic. This is partly because a lot of cargo travels in the belly hold of passenger aircraft. A study from Cranfield stated that in 2013 half of worldwide cargo was transported in cargo aircraft and the other half in belly holds (link). This number has been stable for some time and while it has been expected that belly hold will increase, a 2018 forecast predicts that this will not happen untol 2037 (link).

As per IATA, the airlines represented by the industry organisation transport more than 50 million tons of goods annually. This is just one percent of world trade by volume, but more than a third of the total value. According to a study by the World Bank (link) the price of air cargo is about four to five times that of road transport and 12 to 16 times that of maritime transport. This is why air cargo is only competitive if what is shipped is of high value per unit and time for the transport is an important factor. This means that documents, medicine and medical equipment, perishable produce and seafood, expensive electronics and clothing, emergency spare parts, and inputs to just-in-time production are examples of items which are suitable for being transported as air cargo. The advantage of speed of delivery can be offset against the disadvantage of a higher cost for these types of items.

The COVID pandemic provided an unexpected and large boost for air cargo, with many cargo operators making sizeable profits and many airlines depending on it for survival. This resulted in increased orders for freighter aircraft as well as an increase in conversions of aircraft into freighters. However, the histrory of air cargo is one of dramatic cyclical shift in fortunes, depending on the development of the world economy. What seems safe to say is that, as per a forecast by Boeing (link), the share of air cargo linked to Asian economies will continue to grow for many years ahead (from just above 50% in 2017 to 60% over the next 20 years). A report from just a few weeks ago from IATA (link) stated that cargo volumes increased in August 2021 compared with August 2019, i.e. even when compared with pre-COVID levels. Air cargo demand was 7.7% higher in August this year, again comapred to August 2019 and at the same time capacity was down with 12% in the same comparison, setting up a favourable situation for pricing for cargo operators. The cargo load factor was 54%, which is 10 percentage points higher than in August 2019. Overall, the market situations continues to look good for air cargo and there are some who predict that the increased focus on cargo operations represents a “structural shift” in the industry (link).

From a pilot perspective, transporting passengers has always had a higher status than transporting air cargo. Perhaps because of traditions, pay and other reasons, but also because older aircraft are normally used for cargo operations. With the pandemic and relentless competition and cost pressure among passenger airlines, the difference in status may however gradually be shrinking. Large cargo operators, such as FedEX and UPS, offer competitive career opportunities for pilots. It may be that the old myths about differences between airline pilots and “freight dogs” (link to characterstics of “freight dogs here – link) will surely live on, but during the pandemic many pilots shifted from to air cargo operators and some seem to have found that there are advantages to this type of operation.

This was just a few pieces of information about air cargo and freighter operations, but hopefully we can return to this topic to further explore it. If there are any cargo pilots out there who can provide some guidance and information, or even write a guest post, about air cargo operations that would be warmly welcomed.

Anders Ellerstrand: Procedures 3 – To Assist in Training

This is the third part, in a series of six, about procedures by Anders Ellerstrand. The previous parts are here: Part 0 – Intro, Part 1 – Design Process and Part 2 – Memory Aid.

I cannot imagine a training for someone to be a pilot or an air traffic controller if there were no procedures. Large portions of such training programs are spent reading procedures. To learn about them, to know which of the procedures you need to know by heart and where you will find others when you need them.

Once that is cleared, you spend hours after hours in a simulator where you apply these procedures until you can do it well. Then it is time to apply them in real life, first with an instructor and then, finally, as a trained professional.

I have worked many years as a teacher and instructor, but also as a training manager and I have been a project manager for a new training design. None of these roles would have been possible without procedures. They determine how the training program is designed, how the training sessions are scheduled, how the training results are monitored and assessed and how the training results are validated.

However, there are also a few problems with procedures and training. The most prominent problem is how to deal with the previously mentioned gap between ‘work-as-imagined’ and ‘work-as-done’. Do you recognise these statements below?

• “As you are still in training, you have to do it like this. Later, you will find out how it is really done.”

• “In the real world, you often have to ‘bend-the-rules’ or ‘take a shortcut’ here and there, but that is only fine if you first know the procedures properly. You must know what rule you are bending.”

Sometimes it is not really about bending or breaking, but more about interpretation. During training, you typically have several instructors, and you may find that their ways of using the procedures are different. Do you then adapt, changing the way you operate depending on which instructor you have? Is this a problem acknowledged by the training institute and discussed among the instructors? If it is, it might be that the instructors adapt so that they use the procedures the same way as long as they are in their role as instructors.

A consequence could be if the student sees the instructor performing the real job, doing things differently than he explained it to the student. Then you have the classical parent-child issue: “Do as I tell you, not as I do!”

Good luck with your training! 😉

Recent Comments